Lecture 4. Light, quanta, and atoms

Thursday 25 January 2024

Wave-particle duality. The quantum nature of the atom. Quantum numbers and electronic orbitals.

Reading: Tro NJ. Chemistry: Structure and Properties (3rd ed.) - Ch.2, §2.3-2.6 (pp.89-107).

Summary

Much of our understanding and technical mastery of the physical world around us has come about as a result of careful investigation of the interactions between matter and energy. The development of modern atomic theory from its Daltonian foundation to a contemporary quantum mechanical model provides illuminating examples. In the first glimpses into the inner workings of the atom and its constituent parts, some of the most revealing phenomena concern the interplay between light and atoms. As a prelude to tracing this development, we'll consider the fundamental aspects of light and the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum. Curiously, although light and other forms of EM radiation can be well described as energy propagating as a wave, as shown by the phenomenon of interference, the wave description fails in its ability to account for certain observations such as black body radiation and the photoelectric effect. A quite different model is provided quantum theory, which postulates a quantized nature of light. Ultimately, we learn that EM radiation manifests both wave and particle properties, while matter (in the nano- and picoscale realms of atoms and subatomic particles) also manifests properties of waves.

Light and electromagnetic radiation

The secrets of modern atomic theory have been revealed through careful investigation of the interactions between matter and energy, in the form of electromagnetic (EM) radiation. As we discuss further, EM radiation is a type of energy that propagates through space as a wave, analogous to the waves that travel in water. Waves as periodic, repetitive phenomena can be described mathematically with the parameters amplitude, frequency, wavelength, and speed of propagation. Visible light, the type of EM radiation that our vision senses, is known to elicit the sensation of different colors as the wavelength of light varies. Yet visible light is just a small part of a much larger spectrum of wavelengths. Furthermore, visible light and all EM radiation propagates through empty space with a fixed speed, the speed of light. This in turn makes frequency inversely proportional to wavelength, and the full EM spectrum encompasses radiation from long-wavelength (low frequency) radio waves to short wavelength (high frequency) X-rays. The speed of light (represented as c) is a well determined physical constant,

c = 2.9979 × 108 m/s

and the governing relationship between wavelength (symbolized as λ) and frequency (symbolized as ν) for EM radiation is expessed as

ν = c / λ.

One of our principal objectives is to use this relationship to convert between frequency and wavelength for any given value of either of these. We may also find it necessary to use decimal multipliers for unit conversion, as frequencies and wavelengths of EM radiation vary over many orders of magnitude.

Example: What is the frequency (ν) of visible light with wavelength λ = 535 nm?

Solution: We'll use c = 2.99792458 × 108 m·s−1 the relation between c, ν, and λ.

ν = c / λ.

Since wavelength is given to us in nm, the conversion from nm to m must be included in our calculation:

ν = (2.99792458 × 108 m·s−1) / (535 nm)(10−9 m/nm) = 5.60 × 1014 s−1

In this context, the unit s−1 often gets a special designation, hertz (Hz), so we will also write the answer as 5.60 × 1014 Hz.

Electromagnetic radiation and the quantum nature of energy and matter

Although classical physics had explained most of its behavior as a result of its wave nature, Planck and Einstein showed that electromagnetic (EM) radiation behaves as if its energy is carried at the atomic scale in small bundles of energy called photons with particle-like nature. In other words, EM radiation has a quantum nature. Furthermore, Einstein showed that the energy E, of each of these small bundles, or quanta, of EM radiation of a given frequency ν is given by the following key equation (often called the Planck-Einstein relation):

E = hν

The factor h is known as Planck's constant ( h = 6.62606931 × 10–34 J·s ), an important fundamental constant of nature. If we combine the equation relating frequency, wavelength, and wave speed with the Planck-Einstein relation above, we obtain

E = hc / λ

an alternate form of the Planck-Einstein relation, useful for converting between EM wavelength and energy.

Example: How much energy (J) is carried by one photon of visible light with λ = 535 nm? After finding the energy of one photon of each wavelength, express the energy of a mole of these photons in kJ/mol.

Solution: We'll use truncated values of the following constants (which will be sufficiently precise for the number of significant figures of the calculation input):

c = 2.998 × 108 m/s (speed of light) h = 6.626 × 10−34 J·s (Planck's constant) NA = 6.022 × 1023 mol−1 (Avogadro's number)

Using the relation E = hc/λ (and converting nm to m), we obtain

E = (6.626 × 10−34 J·s)(2.998 × 108 m/s) / (535 nm)(1 × 10−9 nm/m) = 3.713 × 10−19 J

Thus the energy carried by a single photon of 535 nm light is 3.71 × 10−19 J.

The conversion to kJ/mol involves using Avogadro's number and converting J to kJ:

E (kJ/mol) = (3.713 × 10−19 J/photon)(6.022 × 1023 photon/mol)(10−3kJ/J) = 224 kJ/mol.

Exercise: Calculate these same quantities using the value of ν for 535 nm radiation that was obtained in the first example above.

Example: (a) In the

photoelectric effect,

for a certain metal, the threshold frequency ν0, or minimum frequency of EM radiation

that leads to production of a current upon illumination of the metal due to ejected electrons

("photoelectrons") is 6.41 × 1014 s−1.

Calculate the energy per photon associated with light of this frequency.

(b) Suppose this metal is illuminated with light having a wavelength λ = 225 nm.

How much kinetic energy will photoelectrons produced possess?

(c) What is the magnitude of electron velocity for these photoelectrons?

Solution: (a) Use the Einstein-Planck relation:

Ephoton = hν0 = (6.626 × 10−34 J·s)(6.41 × 1014 s−1) = 4.247 × 10−19 J = 4.25 × 10−19 J

(b) In this scenario, the total energy delivered per photon will be calculated according to the second form of the Einstein-Planck relation above,

Ephoton = hc / λ = (6.626 × 10−34 J·s)(2.998 × 108 m/s) / (225 nm)(10−9 m/nm) = 8.828 × 10−19 J

Ephoton = 8.83 × 10−19 J

Note we needed to introduce the conversion factor for nm → m in the above calculation. Next, applying the law of conservation of energy, we reason that the energy required to eject an electron from the metal plus the excess kinetic energy of the ejected electron must be equal to the energy delivered to each metal atom by the 225-nm light. There are several ways to express tis as an equation. The energy required to eject the electron is called ionization energy - in the context of the photoelectric effect this is sometimes labeled as W. We know from part (a) that

W = Ephoton, threshold freq = hν0 = 4.25 × 10−19 J

An expression for the conservation of energy is then

Ephoton, 225 nm = W + KEelectron

which we can solve for the electron's kinetic energy

KEelectron = Ephoton, 225 nm − Ephoton, threshold freq

= 8.83 × 10−19 J − 4.25 × 10−19 JKEelectron = 4.58 × 10−19 J

(c) Here we use the mass of the electron and the formula for kinetic energy, and solve for velocity v of the electron:

velectron = (2KEelectron/ melectron)½

Using melectron = 9.1094 × 10−28 g, and the fact that 1 J = 1 kg·m2·s−2, we calculate the electron velocity

velectron = {(2)(4.25 × 10−19 kg·m2·s−2) / (9.1094 × 10−28 g)(10−3 kg/g)}½

velectron = 9.66 × 105 m/s

which is nearly 0.3% of the speed of light! In this example, we are simply applying the definition of kinetic energy to the electron using its rest mass, and therefore ignoring any relativistic effects.

Quantum mechanics and the atom

A guitar string, or generally speaking, a vibrating string with two fixed end points serves as a one-dimensional analogy to the treatment of an electron bound to a nucleus by the electrostatic force of attraction as a three-dimensional "electron-wave". A mathematical description of a guitar string with fixed length L is a "wave" equation with a set of solutions, or "wave" functions. Such wave functions must satisfy the boundary conditions that the amplitude is zero at both ends of the string. Placing the string on a horizontal "x" axis with one end at x = 0 and the other at x = L, the amplitude must always be zero at these two end points. These conditions allow a series of standing wave solutions with an integral number of half-wavelengths matching L, as the following equation expresses:

½nλ = L, where n = 1, 2, 3, ...

This can be rearranged as

λ = 2L/n, where n = 1, 2, 3, ...

For the electron in an atom, the analogous wave equation solutions (wave functions, Ψ) are three-dimensional and rather than a single quantum number n, these solutions are specified by a set of three quantum numbers (see below). We can think of the quantum numbers as labels, or indices, of the solutions to the Schrödinger equation, and also note that each solution (we'll call these solutions orbitals) is associated with a definite energy E.

Although the wave function Ψ has no direct physical interpretation, its square (Ψ2) is a probability distribution function that describes the probability of finding the electron in any given location relative to the nucleus.

Orbitals for the hydrogen atom

The rules for quantum numbers define the sets of orbitals possible for an electron bound to a nucleus. There are n2 orbitals for any given value of the principal quantum number n. In the case of the hydrogen atom, the energies are determined only by the principal quantum number n, and all n2 orbitals for a given n are all equal in energy (and are therefore termed degenerate). The energy level diagram for electronic orbitals in the hydrogen shown below. In this diagram, we introduce the chemistry convention for naming orbitals according to their set of quantum numbers. The principal quantum number n is retained, while the angular momentum quantum number l is replaced with a set of letter designations (s, p, d, ...).

The distinct energy levels for a hydrogen atom and orbital degeneracies suggest that we can think of groups of degenerate orbitals as organizing electrons in many-electron species into energy-level "shells".

Size, shape, and orientation of the orbitals

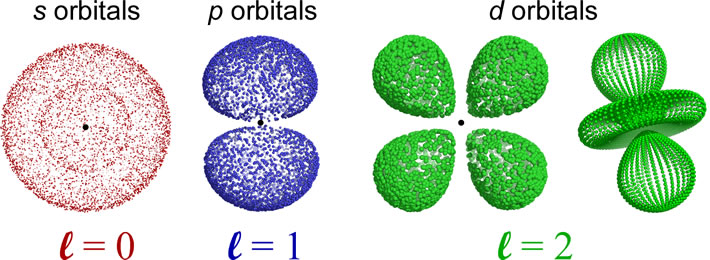

The shapes of the orbitals are determined by the angular momentum quantum number l. The orbitals for which l = 0 are spherically symmetric around the nucleus, and are labeled as s orbitals. For l = 1, a set of three mutually perpendicular dumbbell-shaped p orbitals arise. When l = 2, five so-called d orbitals with more complex shapes are possible. The orientations of the p- and d- and all higher l value orbitals are specified by the magnetic quantum number ml. For further exploration of the sizes, shapes, orientations, and other features such as radial distribution functions, a trip to The Orbitron is highly recommended. Be sure to check out the exotic shapes of f and g orbitals!

Nodes: An orbital will have n − 1 total nodes, with n − l − 1 radial nodes, and l angular nodes. The s orbital depicted is a 2s orbital, and the single node is a radial node. There are no angular nodes in any s-type orbital, since l = 0 for any s orbital. The p orbital depicted is a 2p orbital, which also has a single node, but in this case the node is an angular node - in this case the plane containing the nucleus and bisecting the two lobes of the p orbital. There are two different 3d orbitals depicted - both have two angular nodes and zero radial nodes.